2002 Scheria Hudson Vineyards

Scheria–an island far from the homes of other peoples. Its crushing coastline nearly meant the end and, then, the rebirth of Odysseus. It signifies here a wine that endured oblivion in barrel, that was deemed dead and gone, but that lay entire within itself until it arose after its 24 month in barrel.

“like some lion of the wilderness, beaten by wind and rain, who goes out, sure in his strength, his two eyes burning with fire.” Homer, Odyssey VI.130-132.

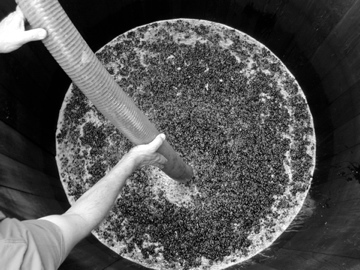

The grapes were harvested on the day before Hallowe'en from Lee Hudson’s Henry road vineyard in Carneros. The clusters remained on the vine until days and nights both became cool and days became short. This imparted a nearly liquorous intensity to the grapes without exposing them to any raisining. The grapes, supple with age, were crushed into an ancient redwood open-top fermenter and punched down only once or twice per day to allow the rich contents of the skins to leach out gently and constantly. After a brief and unremarkable fermentation, the tank was drained by gravity and the skins were pressed by hand, having been shoveled from the tank onto a large metal screen. No hydraulic pressing was performed.

The wine matured so well in barrel during its first year that it became the show-piece of the project’s cellar. In the second year, it turned a terrible corner. I had never topped the barrels and never sulfured the wine. By the Summer of 2004, the wine smelled sharp, nearly sour, and like burnt gunpowder. The once rich fruit now tasted like stewed tomatoes and apple cider. The microbes, too rich with oxygen, had consumed too much of the wine for their own ends, and left nothing pleasant for the rest of us to enjoy. I decided to destroy the wine.

Harvest came early in 2004 and I never had time to spill the four barrels. Finally, in November of 2004, 24 months after that grapes had been harvested, I brought the barrels out of the cellar, onto the crush pad, and gazed at them poised over the drains. I opened one to taste the wine one last time. I had to plunge rather far into the barrel to find some wine. The barrels had never, ever, been topped. And yet the wine had undergone some new metamorphosis. The burnt gunpowder was now fresh gunmetal. Roast coffee, rich dark cherries, chocolate, replaced stewed tomatoes. A generous friend confirmed my judgment that the wine was saved. I racked the wine into an open tank in fresh fall air, added a little sulfur, and returned it to full barrels. The lees, thick like river bottom mud, decoratedthe heads of its newly filled barrels.

71 cases produced.

[Written in 2005.]